The world of conservation, like any specialist area, brings with it a whole host of terms and acronyms that can make it hard to follow and understand. Add in our scientific work, the climate crisis and our involvement in the planning process, and things get even more complicated and nuanced.

To help you navigate the conversations, we take a closer look and explain some of the more frequently recurring terms here. If you have any suggestions for terms to be added, please get in touch.

Old Sulehay Stone Pit

Wildlife protection and area designation

Land that is deemed valuable for wildlife can be designated in a number of ways, some offering more protection than others in the legal and/or planning systems. That protection can be offered by UK, EU or International law, and some offer very little legal protection at all, relying on conventions or charities and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to police and report. Sites can have multiple designations.

We explain some of the most common land designations, and their acronyms, below.

Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI)

This designation is afforded to sites that are representative of the diversity of habitats and rare species in England. These areas are often the best examples of the woodlands, grasslands, heathlands, wetlands, and geological interest of our landscapes. They are protected under the Wildlife and Countryside Act (as amended) and land managers need to work with Natural England to agree how to look after these special places.

Many were originally designated decades ago, and so have a long history of being managed for nature. It needs to be recognised that SSSI were only set up to be a representative sample of important habitats, rather than a way of comprehensively protecting all important places. This is where the role of Nature Recovery Network comes into play, with SSSIs as important areas from which wildlife can move out into the surrounding land.

Local Examples

- Cooper's Hill (https://www.wildlifebcn.org/coopers-hill)

- Felmersham Gravel Pits (https://www.wildlifebcn.org/nature-reserves/felmersham-gravel-pits)

- Old Sulehay (https://www.wildlifebcn.org/nature-reserves/old-sulehay)

- Pitsford Water (https://www.wildlifebcn.org/nature-reserves/pitsford-water-nature-reserve)

- Brampton Wood (https://www.wildlifebcn.org/brampton-wood)

- Dogsthorpe Star Pit (https://www.wildlifebcn.org/nature-reserves/dogsthorpe-star-pit)

- Waresley & Gransden Woods (https://www.wildlifebcn.org/waresley)

National Nature Reserve (NNR)

These are the best of the best of our SSSIs! National Nature Reserves are the areas of greatest value for nature conservation. They are areas that make significant contributions to conservation science and research, where best practice for managing land for nature has been studied, and have helped to shape how we carry out nature conservation in this country. A key part of their remit is to offer a place for the public to enjoy, and have quiet and informal engagement with nature.

All NNRs are also designated (as least partly) as SSSI, and they don’t have any specific additional legal protection. However the NNR designation means that the landowners need to ensure that they demonstrate the principles of best practice in conservation, and have expertise to manage these crown jewels of conservation.

Local Nature Reserve (LNR)

A Local Nature Reserve is an area declared by the local authority as a place in their control where wildlife will be protected, and people can access and enjoy it. These designations don’t result in as comprehensive protection as SSSI, but they do mean that consideration of impacts from development need to be carefully weighed up by planning officers when making decisions.

They’re generally sites that offer habitats that are special in the context of the local area because they offer a place to connect to with a range of natural habitats and species. They can be especially important in urban and suburban areas.

Local Wildlife Site or County Wildlife Site (LWS/CWS)

These are a network of sites that show the most important areas for wildlife in a county. They can be on private or public land, and may or may not have public access, but all have natural features that show the best of what is found in that county.

Whilst they don’t have specific legal protection, the planning system emphasises that they should be protected from inappropriate development. Just because a County Wildlife Site isn’t also a SSSI doesn’t mean it isn’t potentially very important for wildlife – many of our SSSIs were designated in the 1980s, with only a handful of new sites notified across the country each year.

Our CWS network therefore can offer recognition for a host of very important places which hold much of our most wildlife and offer the starting point for our Nature Recovery Network. They are especially important for highlighting newer sites, especially brownfield sites for invertebrates, or sites where significant restoration has occurred in recent time and the value for wildlife can be recognised.

Local Geological Site (LGS)

As well as biological features, sites can be recognised on account of their geological importance, which is where Local Geological Sites come in. These areas capture the importance of the underlying rocks and landforms beneath us, which have so much to tell us about our history, and strongly influences what happens above ground.

The chalk grasslands of the chilterns, the heaths of the greensand ridge, the rich wetlands of the fens, and the river valleys of the Nene and Ouse are all a result of the special geology of our area. Some of these sites are recognised as SSSI, but many more receive LGS designation to ensure that they are recognised in the planning system, and that geological specialists can work with landowners to protect and study these areas.

Natura 2000 sites (aka 'European Sites')

These sites receive some of the highest legal protection, as part of the ‘Natura 2000’ network of sites across Europe. These are protected under the Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2010 in the UK (otherwise known as the Habitats Regulations), and this demonstrates that the site is one of the most important habitats in all of Europe.

There are two types of European Site designation - Special Protection Areas (SPA) are designated on account of their importance for rare and vulnerable birds; whilst Special Areas of Conservation (SAC) offer protection for natural habitats and of wild fauna and flora.

The listed habitat types and species are those considered to be most in need of conservation at a European level. Anything that may impact upon these sites needs to be scrutinised under a Habitats Regulations Assessment (HRA) to ensure that the activity can take place without impacting on the special features of the site.

Special Protection Area (SPA)

A designation in EU law for areas that are internationally vital for birds, whether they breed or migrate here. (See 'Natura 2000 sites')

Special Areas of Conservation (SAC)

A designation in EU law equal to the SPA for areas that are internationally vital for wildlife other than birds. (see 'Natura 2000 sites')

Ramsar

Unusually not an acronym, this is an international designation named after the city in Iran the convention was ratified in. Ramsar identifies wetlands of international importance, especially those providing waterfowl habitat

The Convention on Wetlands, known as the Ramsar Convention, is an intergovernmental environmental treaty established in 1971 by UNESCO, which came into force in 1975. It provides for national action and international cooperation regarding the conservation of wetlands, and wise sustainable use of their resources.

Wildbelt

A new proposed designation in the planning system to accompany other proposed 'zones' in the government's 2020 Planning White Paper. The existing proposed zones are:

- Growth, suitable for “substantial development”

- Renewal, suitable for “development - gentle densification”

- Protected, applying development controls.

An additional Wildbelt zone or designation would enable new land that is currently of low biodiversity value to be designated for nature, and so speed the creation of the Nature Recovery Network (to which the Government is already committed). We envision it reaching into every part of England, from rural areas to towns and cities, securing the future of the new land that we are putting into recovery so that we can reach at least 30% of land in recovery by 2030 and address the climate and biodiversity emergencies. Wildbelt would form a central part of the National Planning Policy Framework review.

- Read the Wildlife Trusts' preliminary analysis of the Planning White Paper (https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/sites/default/files/2020-09/Preliminary%20analysis%20of%20the%20Planning%20White%20Paper.pdf)

- ‘Planning – a new way forward: how the planning system can help our health, nat… (https://www.wildlifetrusts.org/sites/default/files/2021-09/Planning%20report%2024%20pg%20doc_Digital_Spread%20lo-res.pdf)

Using a quadrat during a vegetation survey. - Chris Gomersall/2020VISION

Principles and concepts

Nature Recovery Network

A principle of connected spaces across our landscape - in our towns and cities, on farmland, and in natural places - to give wildlife the opportunity to move between hotspots such as nature reserves and a chance to recover and adapt to pressures like climate change. Accepted into the Environment Bill during its passage through parliament 2019-2021, a Nature Recovery Network would offer a measurable ambition for connected spaces that would be enforced in law, affecting planning and development decisions.

Key to building a Nature Recovery Network is getting in place Nature Recovery Network Maps that show the opportunities for habitat development and creation in key sites that will have the biggest impact on existing habitats.

Living Landscapes

A Living Landscape is one that connects our sites together into a bigger, more joined up area and helps wildlife to move freely through the countryside without barriers. We manage nine Living Landscape projects at the moment, ranging from the Great Fen in Cambridgeshire to the North Chilterns Chalk in Bedfordshire and the Nene Valley in Northamptonshire.

For all of these projects, we work with other conservation organisations, local councils, businesses, farmers, landowners, churches and more to ensure that as much land as possible is managed with wildlife in mind, to help connect our wonderful nature reserves together with the wider environment - and with the people that live amongst and alongside it.

Planning and development

Building work and development has a huge impact on our local spaces, and we work hard to advocate for the best outcome for nature within the planning system. Whether we work directly with local authorities to help them form their Local Plan, respond to planning applications that may adversely affect our green spaces or act as (or with) ecological consultants on specific projects to suggest mitigation measures where needed, the work is vital and ongoing.

The planning system is often seen as complex and dry. Understanding some of the associated jargon can help to cut through.

Local Plan

The plan for the future development of the local area, drawn up by the local planning authority in consultation with the community. Any building work or development projects must be assessed by the local authority in line with the local plan.

National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF)

This is a document created by central government that sets out the planning policies for England and how these are expected to be applied by Local Planning Authorities.

Most recently revised in 2019, there is a searchable version on the government's website.

Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA)

A review of development plan, crucially taken at a strategic level, that is commissioned before specific options have been agreed. In terms of the Ox-Cam Arc, an SEA would look at the impacts on the environment of proposals across the whole area, and have to consider genuine alternatives to them, so that impacts are minimised, and genuine issues about the sustainability of proposals are considered.

If an SEA were carried out unfairly it is open to challenge in the courts.

Environmental avoidance and mitigation; Mitigation heirarchy

Mitigation refers to the concept of minimising or offsetting any adverse environmental impacts of development projects. Plans can be reconfigured to avoid causing harm altogether, or mitigated by reducing their impact all the way to creating new habitat of equal or greater value to wildlife that replaces any destroyed or damaged in the process of building. It is vital to the process of assessing the environmental impact of projects and developments, and comes with a variety of levels of preference, often referred to as the mitigation hierarchy.

Though the most visible outcome of avoidance and mitigation is often offsetting, it is key that this is only used when all other options in the hierarchy have been ruled out. In order of preference, based on how beneficial they are, the hierarchy is:

- Avoid

- Minimise

- Rectify

- Offset

Here’s an example of mitigation hierarchy – including net gain (see below) applied – relevant to bats (with thanks to the Bat Conservation Trust);

- Avoidance refers to choosing options that avoid harm to bats or disturbance of their roost (for example, by retaining a roosting structure through the development design).

- Mitigation refers to measures to protect the bat population from damaging activities and to reduce or remove the impact of development (for example. by carrying out works to a summer roost site when bats aren’t present in the winter).

- Compensation refers to the offsetting of remaining impacts in the form of roost creation, restoration or enhancement as a result of loss of breeding or resting places (for example, by building a new roosting site when the original roosting site is lost through demolition of a building).

- Enhancements refer to providing net benefits for biodiversity over and above requirements for avoidance, mitigation or compensation (for example, the creation of additional roosting sites above and beyond those required for mitigation and compensation purposes).

>> See: Net gain; Biodiversity net gain

Net gain; Biodiversity net gain

The concept that, where a development takes place which leads to unavoidable damage to biodiversity, reparations should be made that lead to an overall improvement for wildlife. For example, where hedgerows have to be removed, more hedgerows of the same benefit to wildlife must be created elsewhere, at the cost of the developer, leading to an overall gain in the amount of habitat, and therefore increasing biodiversity.

There is criticism of the net gain approach because it is felt that it can lead to allowing damaging projects to go ahead. Properly applied, however, it should only apply to projects which do not affect irreplaceable habitats (such as ancient woodland or chalk streams), and which are deemed vital for other overriding reasons.

Although we don’t have assessments of the “net gain” that all developments like our own at Cambourne provide, we are confident from our own monitoring and surveying that they do provide a net gain - though not necessarily to the ideal 20% level. There has, however, been an independent assessment of biodiversity net gain at Trumpington Meadows (commissioned by Grosvenor) which showed a 43% net gain - so we know that it can work.

Reviews of previous developments permitted under current planning rules have consistently shown that they fail to provide net gain for biodiversity overall (see: http://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/POST-PB-0034/POST-PB-0034.pdf for example).

Habitats Regulations Assessment

A specific assessment undertaken to avoid damage to European protected sites - called Special Protection Areas, for birds, and Special Areas of Conservation, for everything else. These include some of our most important wildlife sites, such as the Nene Valley Gravel Pits, and the Ouse Washes.

The assessment is required as projects that damage such sites can only go forward if they are of Imperative Reasons of Overriding Public Interest (IROPI)*. It is important that these assessments are undertaken for development plans at the strategic level - before any decisions or commitments are made - so that options aren’t “locked in” before the risks are understood.

* Examples of IROPI include flood prevention works to protect large urban areas, but also include economic “imperatives” such as port or bay developments (e.g. Cardiff Bay).

Strategic Spatial Plan

This is a plan that reviews development options at a high level. Prior to 2010 when the government removed regional strategies, they were better placed to consider wider sustainability issues, like water supply or combined impacts from recreation, than more local plan reviews are.

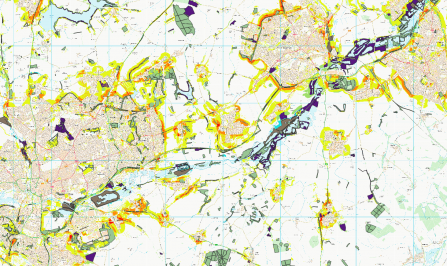

A map of the Upper Nene showing where habitat creation would meet multiple opportunities (e.g. for biodiversity and water quality).

The climate crisis

Conversations around carbon dioxide, targets for net zero and COP26 are strewn with jargon. Here are some of the most common terms and what they mean.

Carbon Dioxide

Carbon dioxide (CO2) is one of the seven major greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change; natural sources include volcanoes, hot springs and geysers. The carbon cycle plays a key role in regulating Earth's global temperature and climate by controlling the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

Emitted in Earth's atmosphere as a bi-product from many different, mainly industrial sources, it's the most significant long-lived greenhouse gas in our atmosphere: emissions since the Industrial Revolution - primarily from use of fossil fuels and deforestation - have rapidly increased its concentration in the atmosphere, leading to global warming and climate crisis.

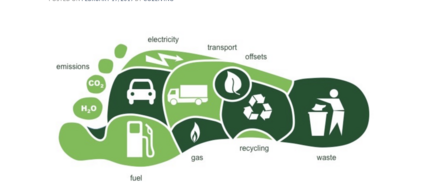

Carbon footprint

Shorthand for someone's impact on the planet: almost everything we do releases greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, from how we travel and heat homes, to the type of shampoo we use. The result of all these actions combined is your carbon footprint, measured in tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent.

Carbon footprint is the total amount of carbon we collectively emit due to all human activities - the total amount of greenhouse gases produced to directly and indirectly support human activities. In other words: driving a car, the engine burns fuel which creates CO2, depending on its fuel consumption and distance driven. Heating a house with oil, gas or coal generates CO2; electricity and the generation of the electrical power emits CO2. Buying food and goods: the production of the food and goods emits quantities of CO2.

A carbon footprint can be calculated or estimated for an individual, an organisation, or an entire nation. The climate change impact resulting from each activity is estimated by calculating the carbon footprint, which includes not just carbon dioxide but also methane and nitrous oxide.

Useful links:

Carbon offsetting

The process of reducing or avoiding greenhouse gas emissions or removing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to make up for emissions elsewhere. Carbon offsetting is a way to compensate for carbon footprint by funding carbon reduction projects in other parts of the world. So, for every tonne of CO2 produced by your lifestyle, you can fund offset projects to reduce the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere by a tonne. Common carbon reduction projects include protecting forests, developing clean energy sources or more efficient energy products. When every possible action has been taken to reduce a carbon footprint, individuals and organisations can offset their remaining emissions to become 'carbon neutral'. There are several accredited schemes for offsetting emissions.

Useful links:

Carbon sink

Any natural place that absorbs more carbon than it releases - soil, forests, peatlands and oceans, when in good condition, all take carbon out of the atmosphere

Useful link:

COP26

COP26 is the United Nations Conference of the Parties (COP) on climate change, now in its 26th year. The first COP meeting (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) was held in Berlin in March, 1995

COP26 in Glasgow (31 October-12 November 2021) will bring together more than 190 world leaders and tens of thousands of representatives to find solutions to the worsening crisis: countries will set out plans to reduce emissions and attempt to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. With the effects of current warming becoming increasingly evident, from record temperatures and wildfires to an increased episodes of heavy rainfall and flooding, climate change threatens people and wildlife.

Useful links:

Nature-based solutions

The use of nature for tackling socio-environmental challenges. Alternative, non-traditional approaches to environmental issues, such as flooding, water scarcity or soil erosion via a wide variety of natural solutions, such as tree planting, peatland restoration and coastal salt marshes. Potentially game-changers for wildlife conservation typically result in thriving ecosystems which store more carbon and help meet carbon-reduction targets while providing homes for a greater diversity of plants and animals. They can also help reduce flood risk or provide much-needed shade as temperatures rise.

Useful links:

Net zero

The achievement of balancing emissions of carbon dioxide to reach carbon neutrality. This means reducing or removing equivalent carbon from the atmosphere to that which is emitted.

In June 2019 the UK government committed to a target of Net Zero emissions by 2050, which means reducing the UK's emissions by 100% from 1990 levels. There will always be emissions that can't be reduced - to reach Net Zero, these unavoidable emissions must be matched by removing emissions from the atmosphere by the equivalent amount.

Useful links:

Carbon footprint