Are we nearly there yet?” How often have you been asked that question? There are several obvious responses: a straight “yes” or “no”; a measure of time – “just 15 more minutes”; a measure of distance – “only 10 miles to go”; a measure of hope – “the sat nav reckons we’ll be there in...” or expectation – “Well, from here it usually takes us...” The outcome still depends on the traffic, the weather, road works and a host of other factors.

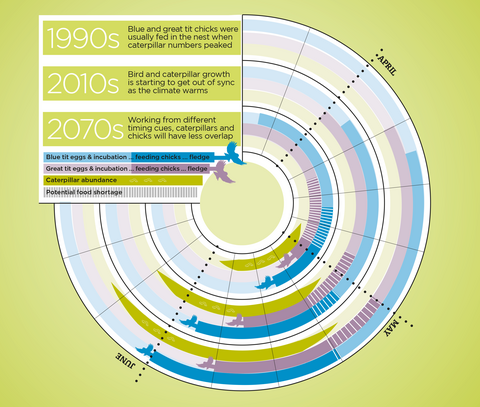

All of these answers have parallels in nature. And the way different species answer that question is not only fascinating, but also lies at the heart of a key issue around our changing climate. In our warming world, the basis for some of the answers is shifting. It also helps to explaining why years with freak weather can be so disruptive for wildlife.

Back to our journey. If everything runs smoothly, our 10 miles could take the 15 minutes that the satnav predicts and that it usually does and could be either nearly there or not depending on your point of view. "Nearly there” may be estimated by time, distance, external clues, past experience or crossing some threshold of closeness.