Being nocturnal bats navigate and hunt, not using vision but sound - although contrary to the popular saying they do have good eyesight. Bats make high pitched calls and by listening to the echoes build up a detailed picture of their surroundings, this system is called echolocation and works the same way as sonar on a ship.

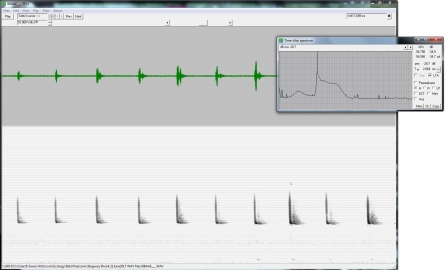

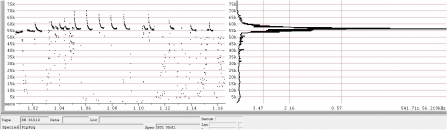

It’s too dark for us to see them (and flying bats are almost impossible to identify to distinguish to species this way) and their calls are pitched too high for the human ear to hear so we cannot simply look and listen for them as we do with birds. Instead we use electronic bat detectors to pick up the bats calls and convert them to audible sound and/or record them.