If you had asked me six months ago to describe a rotary ditcher I’d have given you a very puzzled look. Now, I reckon, I could probably bore you to sleep with the amount of stuff I could spew out about the RSPB’s rotary ditcher (which I’m now going to affectionately call RD), the only machine of its kind in the UK.

Contracted out by RC Baker Ltd., we booked RD to make a special trip to the Nene Valley for a couple of weeks in August, visiting six different sites, managed by seven different landowners to create seven kilometres of ditches, providing tens of thousands of square metres of wetland habitat across the Nene Valley - a veritable Nature Recovery Network.

The background

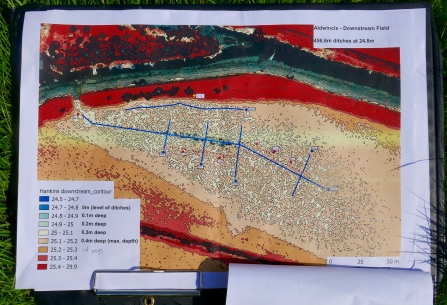

The aim of this work has been to create a series of shallow ditches and scrapes, enabling water to be retained on land beyond the winter months, providing new nesting and breeding spaces primarily for overwintering and breeding waders such as lapwing, snipe, redshank and curlew. Of course, with this new wetland habitat a whole host of other species of fauna and flora will also establish.

The roots of this work can be traced right back to 2002, when a number of sites in Northamptonshire were identified as potential sites for wetland restoration. As part of the Farming for the Future project that I am running as part of the Nenescape Landscape Partnership Scheme, grant funding has been made available through the National Lottery Heritage Fund for conservation work with farmers and landowners. This presented us with a fantastic opportunity to make a coordinated effort to create a series of wetland features across these sites.

The site furthest from the River Nene is at a distance of just 600 metres, and as such, all are regularly affected by, or inundated with water, particularly when the river is in peak flow. Early this year, contact was made with the relevant owners of each site, follow-up visits planned with interested landowners and, just like that, we had project RD up and running.